Safeguarding the mental health of a generation

A year is a very long time in the life of a child. While adults are railing against the constraints of the pandemic, for children the isolation and lack of familiar structure of the past 12 months represents as much as a fifth of their lives. It has become a very unwelcome norm.

And they are struggling: an NHS Digital report published last year found that probable rates of mental disorders among children and young people has increased by almost half since 2017, with Covid and lockdown identified as aggravating factors. Even more upsetting, a national report for NHS England found a “concerning signal” that child suicides may have increased during the lockdown, prompting a warning to doctors and health services to be vigilant.

The pressure on parents and health care providers is overwhelming, with the children’s commissioner Anne Longfield warning last week that young people’s mental health services were “unable to meet demand” in a pandemic. During this Children’s Mental Health Week, we consider whats next for children’s mental health and the importance of population health data in understanding long term impact of the pandemic on mental health and how best to prioritise the delivery of the most effective mental health services to those in need.

Isolation and blame

The rising demand for children’s mental health services was a concern long before the Covid-19 pandemic, prompting the government to commit to NHS-led counselling in schools to up to a quarter of the country by 2023. Mental wellbeing has got worse. The Children’s Commissioner cites an NHS study from July 2020, which found one in six children had a probable mental health condition and said it is highly likely that the level of underlying mental health problems will remain significantly higher as a result of the pandemic, with an increase in referrals to NHS services already observed last autumn.

For teenagers, the lack of social interaction is devastating – as Aristotle said, “Youth is the age when people are most devoted to their friends or relations or companions, as they are then extremely fond of social intercourse…”. At a time when they should be out and about, exploring the world and taking those vital steps away from the ‘safety’ of parents, teenagers are being forced to spend 24 hours a day within family groups.

Not only are children isolated but many teenagers feel they are being blamed for the spread of Covid-19. As Professor Sarah-Jayne Blakemore, author of “Inventing Ourselves, The Secret Life of the Teenage Brain”, wrote recently, “Right now, young people around the world are being blamed and shamed for their role in the spread of coronavirus. In my view, this is not fair and might be counterproductive. Young people are naturally driven to socialise and meet new people and romantic partners.”

Time to Talk

What should be done? Clearly additional investment in mental health services is required. But according to Blakemore, the attitudes of adults and policymakers also needs to shift. She says, “There is evidence that empowering young people to influence each other to make positive and healthy decisions works better than adult-led campaigns. In the case of COVID-19, educating young people about the importance of social distancing and reducing social contact in order to reduce infection rates, and then incentivising them to run their own campaigns amongst their social networks, might have more of an impact than adults lecturing and blaming them.”

The theme of this year’s Children’s Mental Health Week is Express Yourself, a sentiment that is reflected in the adult mental health “Time to Talk” day this February 4th which is focused on getting the public to talk about mental health.

Talking is tough in a pandemic – especially for children who might not want to discuss their problems with parents or siblings. There has been a shift to provide some mental health services digitally. As well as video consultations, online support and the setting up of a new 24/7 mental health crisis hotline, NHS England has set aside £1.4 billion to improve mental health care for children and young people and has said mental health services funding will grow faster than the overall NHS budget with a new fund of £2.3bn by 2023-24.

Population Health

Children’s Commissioner Anne Longfield has confirmed that the quality of services is vastly improved in some areas. However, there is a lack of consistent mental health support for children across the country – and it is vital to understand how this is affecting children.

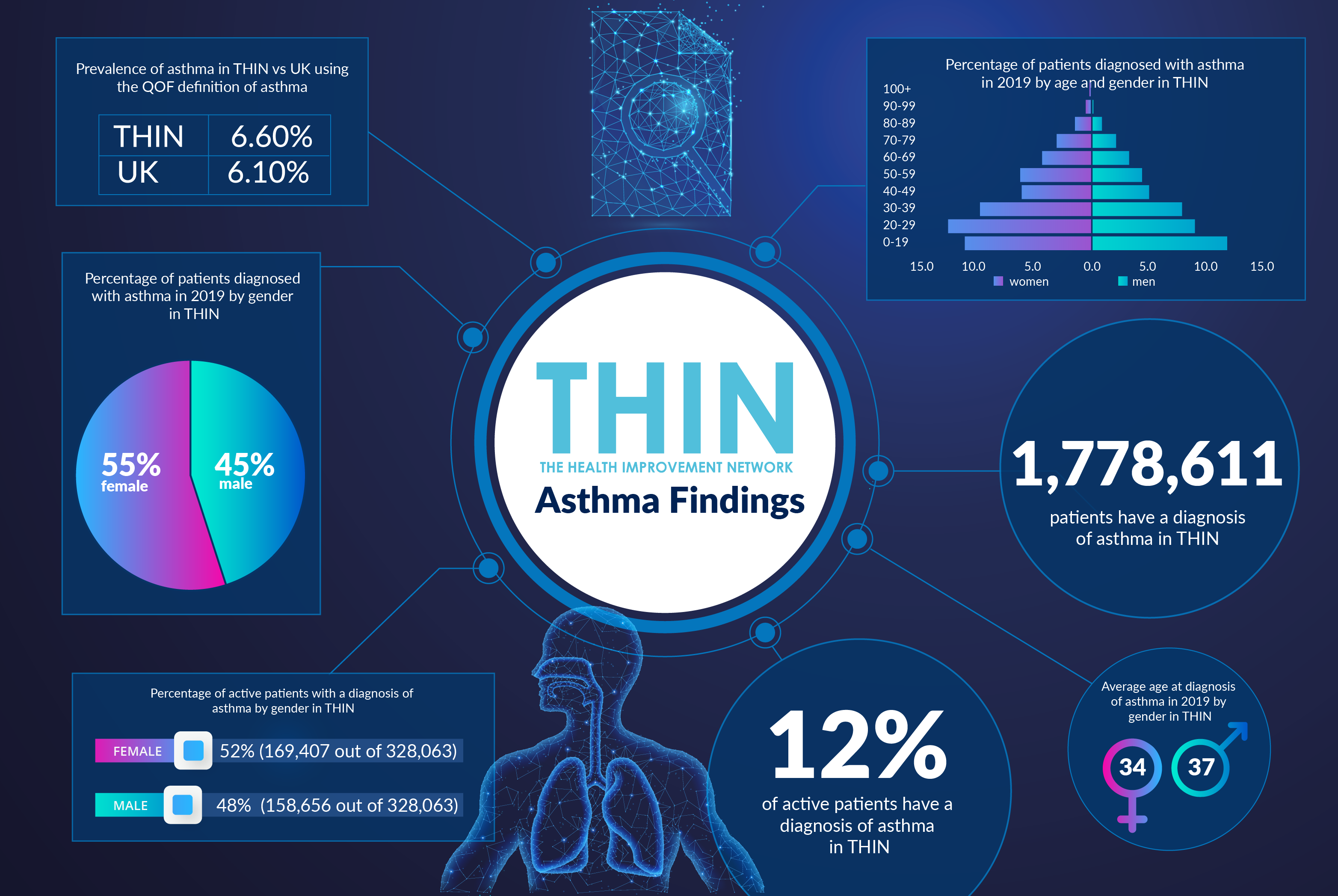

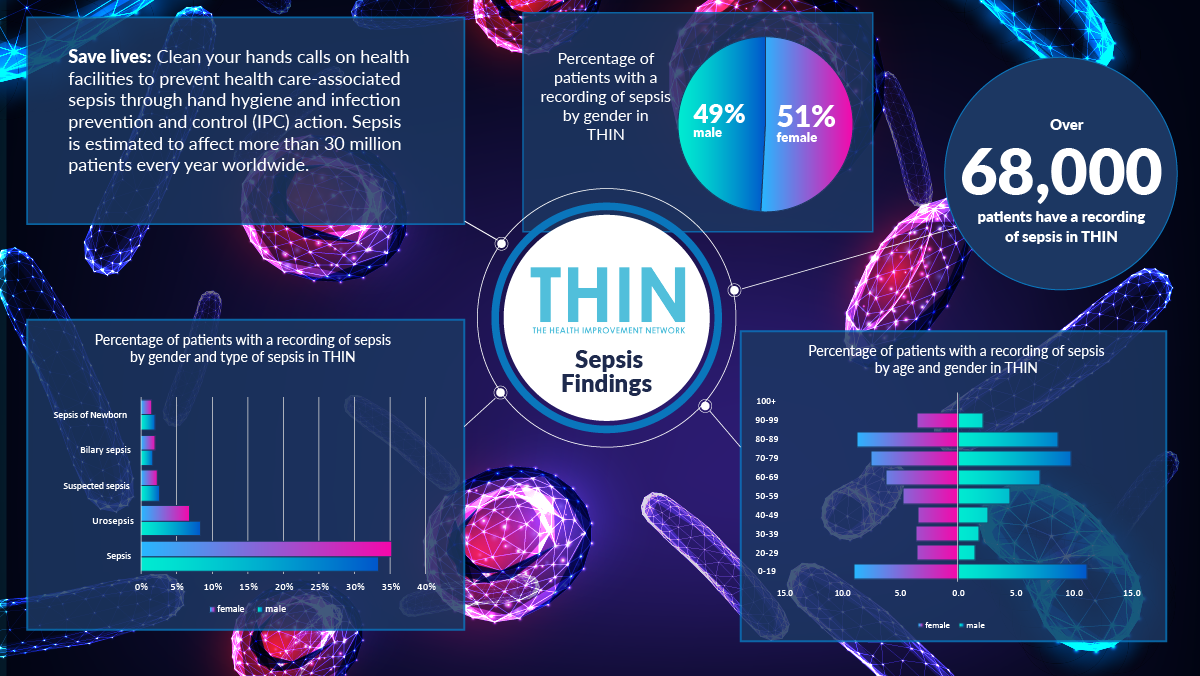

This is where population health data can provide essential insights. Our healthcare systems capture huge volumes of data across millions of touchpoints – most notably clinical consultations in Primary Care. Information captured at this crucial intersection between patient and doctor has huge value when it is coded, structured, anonymised and analysed at scale. The Health Improvement Network, THIN® is recognised to offer one of the most reliable and respected sources of primary care data in the world, with a data set so rich that it brings huge value to healthcare organisations.

There has been no simple, single experience for children over the past year. Indeed while 54·2% of 11–16 year olds with probable mental health problems said lockdown had made their lives worse, 27·2% said it had made their lives better, according to the MHCYP study. While some children struggle with home learning, others are relishing the lack of disruption that can occur within the classroom. Social isolation for some will mean a chance to avoid bullying for others. With schools set to reopen soon, it will be vital to track the progress of children’s mental health, assess the impact of school counsellors and measure the demand on mental health services both digitally and face to face.

Conclusion

This is a crisis. In January a coalition of child health experts warned in a letter to the Observer that “children’s welfare has become a national emergency”. It is vital therefore that everyone involved in supporting children can rapidly prioritise interventions, understand the pros and cons of different care delivery models and put in place the resources that will be required to support this generation for many years to come.