Focus on Men's Mental Health

Every individual has had a different lock-down experience – and for many there has been a notable impact on their mental health. Whether it has been loneliness and isolation, insecurities and fears regarding the financial future, or a lack of familiar routine, lives have been turned upside down. Even as the vaccination programme continues at pace, many questions, concerns and anxieties remain – and, it is becoming clear, there is a very significant section of the male population that is failing to call for help.

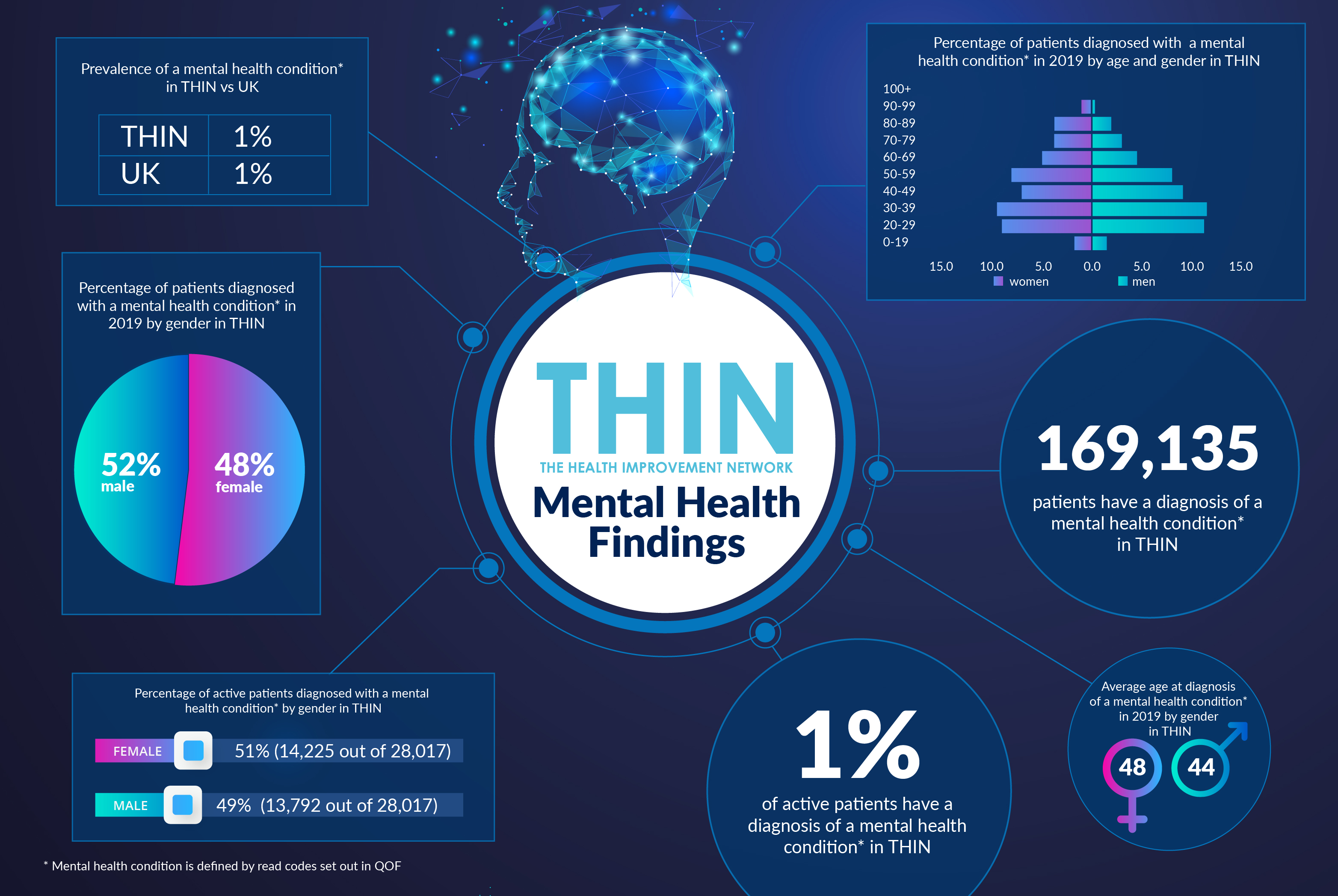

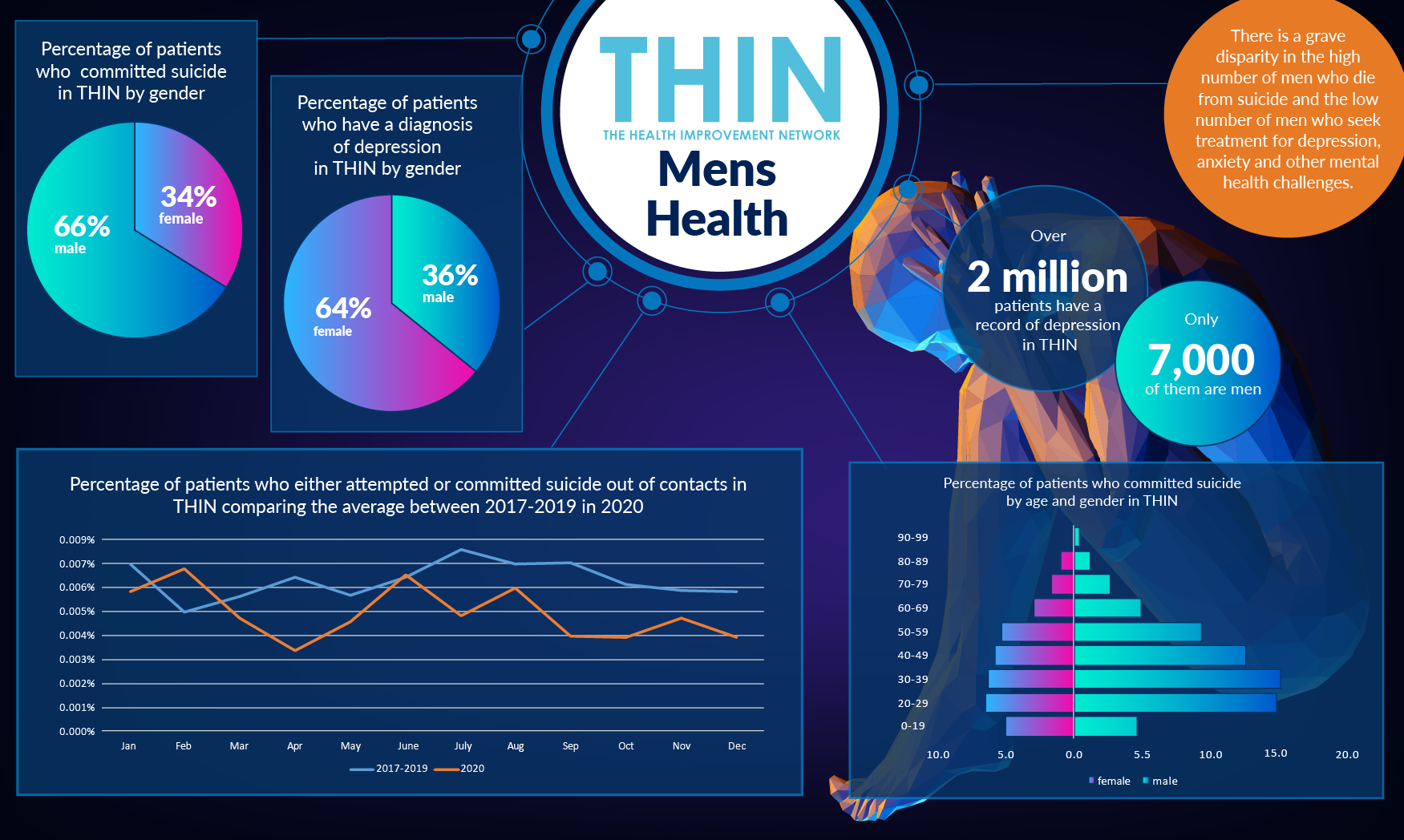

Even before the pandemic, there was a grave disparity between the high number of men who die from suicide and the low number of men who seek treatment for depression, anxiety and other mental health challenges. Analysis of The Health Improvement Network (THIN®), a Cegedim database, reveals that men make up two thirds (66%) of individuals who committed suicide.

This year, during International Men’s Health Week 2021 (14th – 21st June), the discussion is focused on the steps that can be taken to move forward.

Pandemic Impact on Mental Health

According to the Samaritans, men are three to four times more likely to die by suicide than women in the UK and Ireland. Furthermore less well-off men living in deprived areas are up to ten times more likely to die of suicide than men living in more affluent locations.

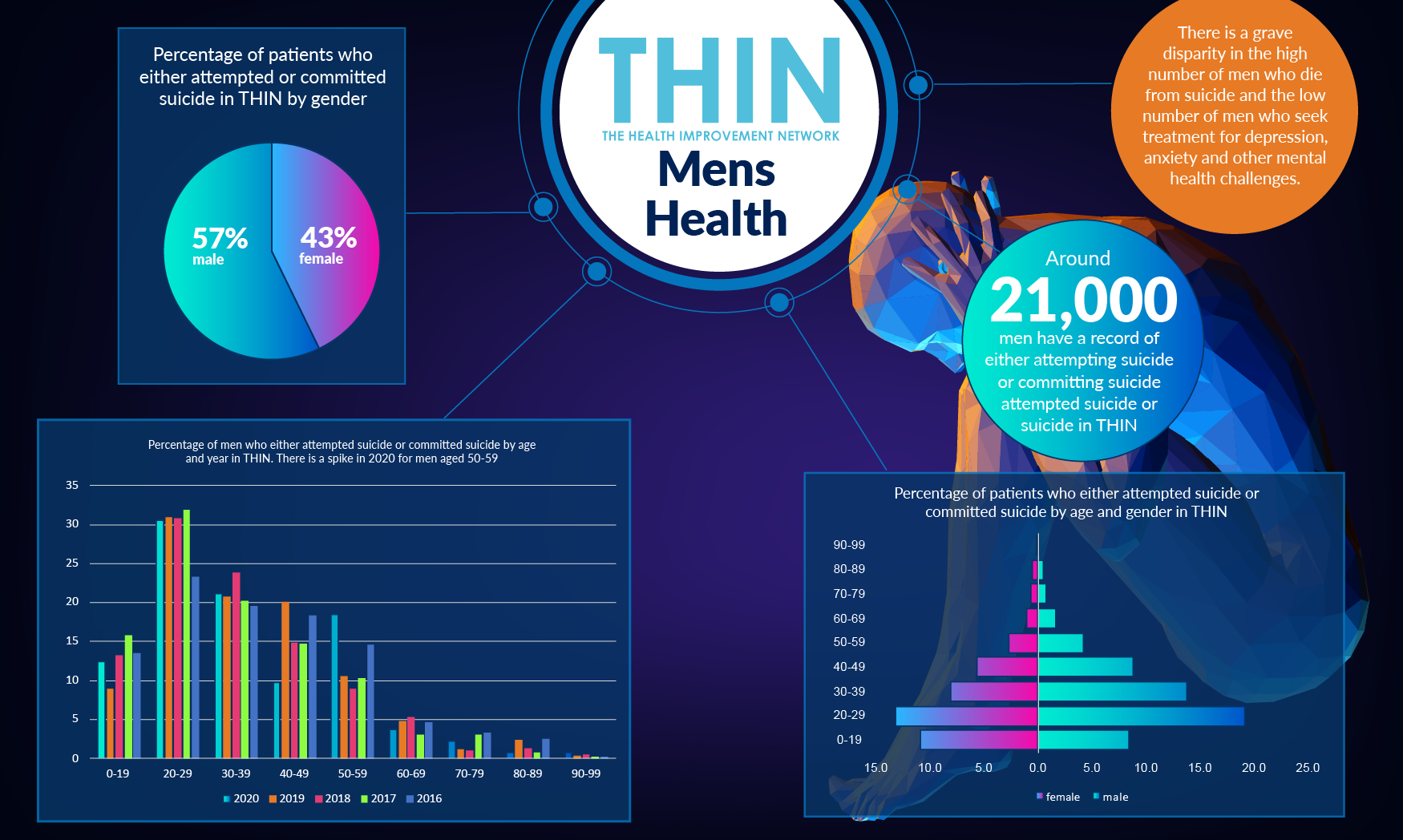

Analysis of THIN® data also confirms that men are more likely to succeed in a suicide attempt than women – while women make up 43% of those who attempt or commit suicide, that drops to just 33% of those who actually commit suicide. In contrast, when looking at patients who have a diagnosis of depression in THIN®, the majority (64%) are women, underlining the fact that men are less likely to ask for help. Over two million patients have a record of depression in THIN®; only 700,000 of these are men.

Suicide rates in men are higher in middle age, with suicide the highest cause of death among men under the age 45. Analysis of THIN® data actually reveals that more men aged 20-29 attempt suicide – although during 2020, the data reveals a spike in men in their fifties attempting to committing suicide.

Risk Factors

Not enough is yet understood about the most effective interventions to support men who are struggling, which is where population health data such as THIN® is so important. Certainly it appears that particular groups of male-dominated workforces have suffered disproportionately in terms of income during the pandemic and not all have received support from government to compensate for this loss. Men are more likely to be in the sort of jobs that cannot easily be done from home with the result that many male-dominated workforces are also at greater risk from Covid-19.

One of the problems in addressing and reducing suicide is that it is a complex behaviour, with a range of risk factors. In addition to prior suicide attempts and known mental health problems including depressions, relationship problems, social isolation, bereavement and physical illness or disability are all known risk factors – many of which have been heightened during the past year.

In addition, male suicidal behaviours are often linked to external factors, such as business failure and/or a forced retirement, thus suicide-prevention plans need to take into account individual internal or psychological factors such as feelings, personal shortcomings, or relationship issues.

According to an article by Dr Funke Baffour, Chartered Clinal Psychologist, there is a risk that health professionals overlook the signs of depression, especially in older men, focusing in other problems such as heart disease, which can cause depressive symptoms, as well as medications that can have depressive side effects.

Social Prescribing

Research from the Samaritans suggest there are critical opportunities missed to help men before they reach crisis point. The charity concludes that by the time they reach middle age, the men were missing social connections and lacked meaningful activity with offered purpose in their lives. Isolation is a big issue - men wanted inclusive initiatives based on peer support and shared experiences, also purposeful goals which give the chance to work towards a common aim and the opportunity to make a contribution.

One of the key recommendations is the need to keep occupied, which is where social prescribing has a powerful role to play. A key component of Universal Personalised Care, social prescribing, also sometimes known as community referral, is a means of enabling health professionals to refer people to a range of local, non-clinical services. The referrals generally, but not exclusively, come from professionals working in primary care settings, for example, GPs or practice nurses.

Recognising that people’s health and wellbeing are determined mostly by a range of social, economic and environmental factors, social prescribing seeks to address people’s needs in a holistic way. It also aims to support individuals to take greater control of their own health. Schemes delivering social prescribing can involve a range of activities that are typically provided by voluntary and community sector organisations. Examples include volunteering, arts activities, group learning, gardening, befriending, cookery, healthy eating advice and a range of sports.

Understanding Strategies

According to the King’s Fund, there is a growing body of evidence that social prescribing can lead to a range of positive health and wellbeing outcomes. Studies have pointed to improvements in quality of life and emotional wellbeing, mental and general wellbeing, and levels of depression and anxiety. For example, an evaluation of a social prescribing project in Bristol from the early 2010s highlighted improvements in anxiety levels and in feelings about general health and quality of life.

As the NHS faces an expected escalation in demands on mental health services post pandemic, population health data such as THIN® can provide vital insight to improve the physical and mental health outcomes of individuals. It will help to refine strategies, including the role of social prescribing, and deliver essential insight into the potential ‘missed opportunities’ to engage with men before they reach a crisis identified by the Samaritan’s research.